Models of care: The future

In this section, we discuss the key considerations for shaping future paediatric care models.

Twenty years is a long time to think ahead. This project reminds us of the need to be brave and to face up to doing things differently. It takes courage to admit that perhaps we are not doing things as well as we could. We all work hard, but perhaps just not in the right way.

Change is difficult, both from a personal point of view and from a job structure and organisational perspective. There are often competing agendas, which means that the way we offer services can be incohesive, leaving gaps for children and families to fall into. We too often offer services that suit us and not what patients are asking for. We are hearing more frequently that young people want to be seen in schools and environments where they feel empowered to be themselves and talk, in the community that is important to them.

There are many external drivers for change in paediatric models of care in the UK:

- We are not meeting children’s needs, with poorer health outcomes than comparative populations

- Poverty continues to increase, and although healthcare is free at point of contact, getting to that contact is increasingly difficult for families

- We increasingly need to consider the environmental impact of the way we deliver services

In the future, we think that the underpinning philosophy should be that all paediatric models of care are child centred. There are five key areas for consideration, or five questions, that should be asked when deciding on the model of care that is appropriate Throughout this document you should reflect on these areas and consider your own environment, producing a model of care that produces best outcomes for children.

Figure 8: There are five key areas for consideration, or five questions, that should be asked when deciding on the model of care that is appropriate, keeping the child or young person at the centre.

Integrated services

There are very few things in life that exist in isolation and paediatric services are the same. As humans, we constantly have to look to our environment, identify any changes and modify our approach when needed. Communication and adaptation are key ingredients in any system.

The World Health Organisation definition of integrated care is ‘health services organised and managed so that people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways that are user friendly, achieve the desired results and provide value for money.’

Integration replicates physiology, where you are constantly in touch with others around you who are essential for your service to be effective. Consequently, there will be themes throughout this work related to either horizontal, vertical or longitudinal integration. We haven’t referred to them specifically – they are artificial terms to attempt define what is effectively working together with other parts of the health care system and partner organisations. But for those who are interested:

- Horizontal integration is between health and partner organisations such as social care and education,

- Vertical integration is between those services out of hospital and those inside hospital and shouldn’t just be restricted to integration of secondary and primary care;

- Longitudinal integration reflects services linked over time, e.g. transition into adult care.

Thinking now about the future of integrated care. The 2019 NHS long term plan encourages discussion regarding extension of paediatric and young people’s services up to and including the 24th year, which will require much thought and collaboration with adult services across health, social care and other organisations such as those in the education sector.[1]

Getting health services right for adolescents is of critical importance, as it is during this period that many long-term health conditions emerge, and associated behaviours can have most impact. Offering developmentally appropriate care with the ability to adapt to changing biopsychosocial profiles, and addressing physical, sexual, social and mental health needs in consultations, will be important.[2] Dedicated young people’s clinics, specific ward areas, the presence of youth workers and a multidisciplinary approach are all considerations, as well as integration with primary care and adult physicians. The RCP has a toolkit which sets out some broad categories and reminds us to consider information sharing, professional responsibilities and confidentiality.[3]

Integration is also essential for children and young people’s mental health services, where unfortunately there is far too often a disconnect between community services and children’s psychiatric inpatient units. At the moment each of these are seen as separate entities, where each is a separate step rather smooth overlap. Inpatient units are often seen as useful for an acute break rather than a last resort, and the CQC report ‘Out of sight- who cares?’ 2020 identified a hidden population and segregation of vulnerable young people, especially with autism.[4]

We also need to better understand the child in context of the family, as failure to do this means that the care we offer may never be effective. A good example is asthma care. If I prescribe inhaled corticosteroids twice a day for a six-year-old, who will be present at both ends of the day to supervise administration? Are inhaled corticosteroids acceptable in terms of cultural identity and for the child – will they take them? We do not examine our practice in this way enough. Some would say it’s not their role – but if we are to be effective as doctors, we need to have enough oversight to ensure that questions like these are being addressed within our service. In this situation, having both horizontal and vertical integration would enable access to better support for the child and family (e.g. support from primary care and school).

A whole population approach to care

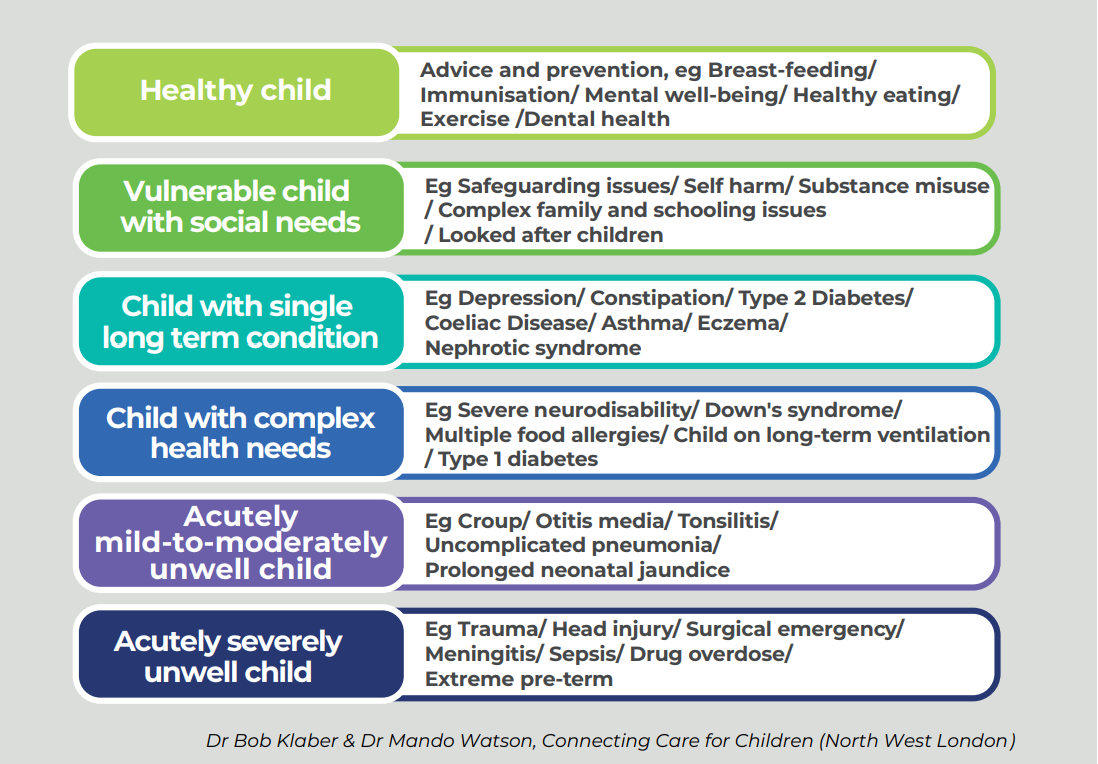

In the future, we want to see a whole population approach to care. There are six broad patient segments which can be used to inform the patient pathway.[5] Service themes (such as safeguarding, mental health care, transition) cut across all of these segments. Our recently published document on the future of paediatric training[6] supports this vision and sets out how placements in the future paediatric training pathway should encourage all trainees to identify opportunities to develop their expertise in management of all patient segments and the themes that cut across them.

We are going to consider each of the following themes in turn:

- Healthy child

- Vulnerable child

- Child with a single long term condition

- Child with complex health needs

- Acutely mild-to-moderately unwell child

- Acutely severely unwell child

We have also tried to share best practice examples within each theme. These are not exhaustive and we are aware there are many models around the UK that may be doing similar work.

The healthy child needs to stay well. Across the UK, we need a clear agenda to ensure the welfare of children is a part of central and local government plans – alongside a clear focus on families in order to reduce inequalities and the proportion of children living in poverty. Early years intervention concentrating on the first 1000 days of life from conception through to two years is a critical time to prevent physical or psychological harm from developing as well as concentring on reducing exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that can impact on long term health attainment.[7] Education is central to improving life chances, and ill children too often experience a reduction in educational opportunities. Hence horizontal integration between health services, local government (social services) and education is needed to provide and maximise opportunities for all children.[8]

Public Health and Prevention

At the time of writing, Public Health England is responsible for delivering the prevention strategy in England for neonates, children and adolescents, with Public Health Wales in Wales, Public Health Scotland in Scotland, and the Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. These bodies are responsible for making the public healthier and reducing unwarranted variation between different groups and areas of the country by promoting healthier lifestyles, advising government and supporting action by local government, the NHS and the public.

The Public Health and Prevention subgroup of the Children and Young People’s Health Outcomes Forum (an independent advisory group of professionals and representatives from across the children’s sector who advised government on how to improve children and young people’s health outcomes from 2012-2016) published guidance in 2012 on how the health system can promote the wellbeing of infants, children and young people by acting early and encouraging support from their families to lead healthy lives.[9] Many of their key indicators have not been developed further and still need information technology systems in place to accurately gather information to help support service development regionally and locally.

Health literacy refers to people having the appropriate skills, knowledge, understanding and confidence to access, understand, evaluate, use and navigate health and social care information and services. We know that across all social groups, illness is a time when people struggle even more with health literacy and hence it needs to be built into every encounter, with a focus on health promotion and developing/improving decision making tools for parents. A failure to understand and evaluate allows misinformation to spread, particularly around the health prevention arena – such as with vaccination and managing obesity. A proactive approach is required to promote literacy within health such as the ‘read out and read program’ and we need to consider how education and health work together within integrated care systems.

Examples

Healthy Child Programme

The Healthy child program 0-19 is commissioned to provide the best start in life and beyond with local systems being responsible for ensuring implementation.[10]

Surrey Heartlands

There are some integrated care systems that have developed best practice, with Surrey Heartlands being one of the first to engage with a system wide dedicated maternity advice line staffed by midwifes that has seen reassured mums call ambulances less and reduce attends at local maternity units.[11]

Hampshire

Use of a ‘training the trainers’ package for primary care professionals via the Healthier Together Website to facilitate improved knowledge in new parents for minor health conditions in children. This resulted in fewer emergency department attends in this group compared with those who did not receive the educational material.[12]

Texas Reach out and read

To promote literacy in general, the ‘reach out and read program’ in the US supports engagement in reading at all ‘well child’ visits such that health care staff are trained in this engagement program and the reading age of children has improved prior to starting school. This approach supports early intervention work to promote educational attainment and life chances by understanding parental literacy and their ability to read to their children.[13]

Dental Health

Dental caries are common in children across the UK, and are associated with infection, pain and altered appearance and quality of life. They are strongly associated with deprivation. As part of a preventative health approach, paediatric services should assess the presence of caries and deliver consistent, structured and supportive preventative messages, as well as signpost to dental professionals when required. Outpatient and inpatient areas are opportune places to consistently offer dental health messages.[14]

Community and Developmental problems

The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in referrals to child development centres (CDC) or child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) when there are concerns regarding social communication disorders, such as autism (ASD) in children, behavioural issues and attention deficient hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Throughout the United Kingdom the services offered for community, neurodisability and allied CMAHS differ depending upon place, which means it is difficult to generalise on appropriate models of care.[15] However, the pathways for these children are complex, often involving social services and education as well as medical provision.

The failure to provide timely and effective services increases the vulnerability of these children, resulting in increased risk of harm especially to their mental health and resulting risk of self-harm and suicide. Their social vulnerability is evident in multiple environments[16] and pathways that ensue. Timely diagnosis and intervention are needed to ensure educational attainment is achieved, alongside a reduction in social vulnerability and improved mental health. There is evidence that integration of services with a multidisciplinary team-based approach – where competencies are more important than role definition – results in a timely cost-effective service provision with improved health outcomes.

Example

Integrated Service Mid Sussex Child Development Centre

Prior to referral, families are supported through early years help with parent training programs. Classroom observations are undertaken by a mental health nurse, meaning the school can start to implement a needs-based approach. A general developmental assessment occurs and if joint pathology is suspected, a referral is made to the integrated pathway where CAMHS practitioners support the service and facilitate early dual diagnosis of ASD and ADHD. This reduced both time to diagnosis and cost, especially as allied health professionals are utilised for their skills rather than doctor-based diagnosis being the only model.

Child with Social Needs

Vulnerability expresses the possibility of harm from emotional or physical causes and is often within a child’s immediate environment. These may fall into one of two areas:

- A child has a social communication disorder that is undiagnosed and means strategies for management are not put in place, resulting in poor educational attainment and emotional harm.

- Children are not responsible for the environment they are born into.

- A child may have a medical diagnosis where the care givers are unable to meet the child’s needs, resulting in harm. This needs to be thought about in each encounter, acknowledging the biopsychosocial impact of a care givers own needs and abilities on their ability to engage with management plans and child health outcomes.

- A child is born into a household where members of the household have needs such as alcoholism that cause toxic stress. There is an acknowledgement that childhood exposure to ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs) results in increased risk of poor childhood development and impact on the life course.[17] These effects are dose responsive and cumulative – however they are not linear, as resilience factors are protective. Nurturing families embedded in strong neighbourhoods and communities can mitigate the effects of ACEs.

- Deliberate harm can occur in a child’s life and effective, responsive child protection services (including those for looked after children) need to be present.

Models of care need to take the above into consideration and explore social circumstances in all encounters that include personal and community factors. By working in an integrated way with social services and education, intervention can occur early – either at the level of a neighbourhood, place or across an integrated care system. At a basic level, this means questions can start to be asked at each encounter, beginning with a simple question such as ‘Has anything scary or upsetting happened to you or your child or your family since the last time I saw you’ and moving towards a more formal evaluation within a screening tool. Many approaches are novel, and outcomes need to be continually evaluated.[18]

The majority of deaths were previously in those children acutely unwell from infectious disease with no underlying morbidities. The number of children with a single long-term health condition has increased significantly over the last two decades, with asthma, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, eczema and epilepsy contributing. Now, between 60% and 70% of children who die in the UK have a long term condition.[19] Some are conditions that require continual monitoring whilst others will fluctuate over time. This has meant an adaptation of paediatric services to care for a different population of children that has yet to be fully realised

The impact on both families and carers, including paediatricians, of caring for a child with on-going health needs has to be taken into consideration, as well as the impact of social complexity on the ability to deliver care and societal expectations. For these reasons, and the increase in practical, ethical and moral dilemmas associated with looking after children with long term health needs, the integration of services has never been needed more, in addition to more effective mapping, co-ordination and communication between services. Alongside this, the availability of an effective expanded paediatric workforce that is supported within organisations will be integral to delivering high quality responsive sustainable care for patients. This includes not only a multidisciplinary team, but support from services such as ethics committees and Schwarz grand rounds to discuss human factors and create empowered, mentally strong health care staff.

Coding

To help understand and deliver the most effective and efficient health care services, we need to be able to differentiate the needs of the children. Coding is a way of understating the complexity of patients with ICD10CM and the international SNOMED-CT allowing a single clinical terminology to be allowed accurately and consistently across all health care settings. SNOMED-CT is a standardised, comprehensive vocabulary that allows clinicians to accurately record patient data at the point of care and share information across health systems. Roll out is active across England, and there is lots of information about this on the RCPCH website.[20] The devolved nations are also actively involved in SNOMED-CT appraisal and adoption, although there are no clearly published timelines.

Networked model

A number of new care models have developed to reduce clinical variation for single long term conditions to ensure the child is seen in the right place at the right time by the right professional. The intended benefits include improved health outcomes, reduced morbidity and improved quality of life, and reduced use of unscheduled and scheduled care through promoting a proactive management strategy rather than a predominantly reactive approach.

The models of care for diabetes, with a networked national strategy, would benefit other conditions such as asthma which still has mortality and morbidity rates in excess of comparable countries. The difference, however, is all children with diabetes will remain under consultant care until adulthood whereas children with asthma may require more of a vertical integrated approached with escalation when required. The escalation and clinical pathways for asthma and many other long-term conditions are diverse across the four nations, some of which may depend upon services available, however there is far too much unwarranted clinical variation which is in part also due to non-adherence to clinical guidelines.[21]

Examples

Connecting Care for Children

Connecting care for children (CC4C) is a vertical and horizontal integration model developed in north west London by paediatricians at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, in partnership with a wide range of other stakeholders. The starting point of the Child Health GP Hubs in 2014 was around groups of GP practices serving a population of approximately 20,000, where 4000 are children. Since the development of Primary Care Networks (PCNs) the model has been adapted to run one hub within each PCN. The team are currently running hubs in six local PCNs and have plans to extend the model across the emerging integrated care system (ICS). The model was developed with extensive stakeholder engagement and co-design with three main elements of a joint clinic delivered in primary care by a paediatrician and GP, and a regular multidisciplinary team meeting which other health care professionals may join. It also features ongoing availability of paediatricians via a telephone hotline or email to support primary care colleagues in their decision making. The open access component extends to families who are able to have same day review by primary care staff, and there is a strong culture of community engagement and co-production throughout the programme.

Triage Process

Nottingham University Hospital have taken a different approach with consultant paediatricians being employed to review all new referrals into the organisation. This has meant that the right child is seen in the right clinic at the right time.

Advice and guidance initially developed in Musgrove General Hospital used the IT referral system to ensure that primary care had access to paediatric consultant advice that resulted in simple advice being given and less new clinic appointments.

BeatAsthma

BeatAsthma[22] is now the agreed approach to paediatric asthma care in the North East, with every secondary care trust and growing numbers of primary care networks using the standardised approach and resources. This ensures every child receives the same message in the same way, wherever they go to receive it.

BeatAsthma is a collection of over 150 resources, with different portals of entry for health care professionals (primary and secondary care), schools, families and teenagers. In each portal, there are a wealth of resources, designed and written by the people who would use them, to facilitate excellent asthma care. There has also been dedicated training for health care professionals and school staff, and information bundles for families and young people where the fundamentals of asthma education and care could be delivered in a single session.

Since the start of interventions, unplanned hospital attendances in young people due to asthma in Newcastle have reduced by 29% and this has been sustained for the last 3 years. This is on the background of a region-wide increase of 10%. A pilot project (BeatAsthma+) is currently underway. Using a digital triage tool, embedded into primary care IT systems, they have been able to automatically identify those children at increased risk of adverse asthma outcomes and invite them to join a new pathway where they are offered interventions over a 1 year period.

Children and Young People’s Health Partnership – the biopsychosocial model

CYPHP (Children and Young People’s Health Partnership) is a new model of care in South London, with a substantial clinical-academic programme of health system strengthening behind it. The model is bio-psycho-social care and population-based early intervention, delivered in the community through primary care networks and children’s centres, by a multidisciplinary team with an emphasis on children’s specialist nurses.

Health system strengthening:

- Governance models for shared decision-making and coordinated action, this means the model is commissioned gradually to demonstrate impact

- Financing instruments that incentivise cross-organisation and sector working.

- Technology including a patient portal that supports self-referral for increased access, pre-assessment screening to support triaging and tailoring care, population health management tools for case finding and early intervention, and inter-operable systems and shared clinical notes.

- Analytic systems that enable prediction modelling of demand and need, service and workforce capacity.

- Education and training for multidisciplinary working and novel nursing models.

- Services as above, delivered by whichever team member(s) most suitable for the child and family. This can be paediatrician, GP, mental health, social care, emphasis on community nursing. All families receive health promotion and supported self-management information.

Evaluation included:

- Service evaluation reporting quarterly on outcomes and costs for commissioners and providers

- Research evaluation (cluster randomised control trial) for rigorous outcome measurement of health impact, healthcare quality, and health service use across primary and secondary care.

Results from service evaluation demonstrate improved health, healthcare quality, and reductions in service use that produce cost savings reduction in inequalities in access to care – so the sickest and most deprived are receiving care earliest.[23]

Non communicable disease accounts for the majority of disability-adjusted life years lost in young people in Europe. Children with medical complexity (CMC) have medical fragility and substantial functional limitations with physical, developmental, emotional and/or behavioural needs that need to be met. There is a significant knowledge gap relating to incomplete and imprecise definitions of CMC and although CMC account for a small proportion of children they account for a significant proportion of healthcare resources. As such the concept is just being developed with UK partnerships such as CoLAB developing workstreams to meet these needs in partnership with children and families.[24]

The advent of SNOMED-CT needs to allow a depth of coding across primary, secondary and tertiary care such that common care webs can be identified and allow service intervention to reduce variation and improve outcomes. In the US there has been a rapid development of structured complex care programs but few well controlled studies that allow comparison. Also in the US, a medical complexity algorithm has been developed based on ICD9CM.[25] This gives a common condition description for children with complex health needs, children with non-complex health needs and children without long term health needs, alongside potential examples. We hope in the future to see something similar for UK patients.

There are principles that all services need to incorporate to be effective. These are:

- Care mapping

- Care co-ordination

- Responsive care

- Ethical/Moral imperative

- Communication

We need to be clear that any new model of care for children with long term health problems is an ‘enhanced care model’ that will improve both quality of care and quality of life, as well as experience measures for families, patients and health care professionals.

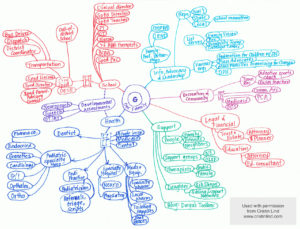

Care mapping

Families have developed tools to allow them to navigate complex systems with multiple health care providers as well as interaction with social care. These tools could be helpful for professionals in allowing them to better understand families’ needs and strengths. A self-identified care map allows families to create a visual model of their child’s entire care team, as well as identify gaps and strengths. This is an example from a family member who created one such map and who worked together with Boston Children’s hospital to share this method with other families.

Used with permission from Cristin Lind, http://www.cristinlind.com

Care Co-ordination

The care map above identifies multiple systems involved in a child with complex medical problems. The complexity of the system means that parents struggle to understand access points and know who is responsible for ensuring their child needs are met for a particular problem. Within the NHS you have medical secretaries, waiting list co-ordinators, outpatient co-ordinators and junior medical teams who frequently change and do not know the child. There is infrequently a lead clinician who is responsible for care co-ordination and delays in access can result in delayed treatment, which often increases morbidity and contributes to mortality. Lack of knowledge also contributes to over medicalisation, with some children with complex needs having excessive investigations and treatment which themselves may contribute to poor health outcomes.

Comprehensive care plans can be a useful way of solving this.[26] Having a responsible individual who knows the child and can co-ordinate the care or a dedicated organisation hotline for families to use for directed care improves access, satisfaction and self-efficacy for the CMC and family.[27] The RCPCH facing future standards for children with ongoing health needs also refer to this, and go into more detail on the standards that all paediatric services should be meeting to support this group of young people.[28]

Responsive care

Children become unwell very quickly especially if they have reduced resilience through long term health problems. It is important that when a child, particularly one with underlying health needs, becomes unwell, they have access to a knowledgeable health care professional who can access and treat the illness in a timely fashion without the need to navigate a complex system.

Ethical/Moral Imperative

Within healthcare there has been a rapid development of assisted technologies that allow the prolongation of life. Many medical conditions which would have previously been significantly life limiting or incompatible with life such as neuromuscular conditions now have mechanical systems that can support and extend life. The question at times is whether prolongation of life is the ultimate goal or whether the main focus should be on quality of life and who ultimately should decide. Conflict has arisen in some cases, causing distress to families and health care professionals and resulting in the breakdown of trust and relationships. A strategy for intervention at an earlier stage is needed using medical ethics committees and communication interventions.

End of life care is currently offered in a non-cohesive and un-coordinated manner across much of the United Kingdom, however there is much change involving organisations such as ‘Together for Short Lives’[29] and NICE guidance that aims to improve delivery of a moments of care which will be remembered forever by involved families and health care professionals.[30] System co-ordination will ensure that families have access to an emotionally secure environment that is able to meet the young persons and families need at a difficult time. Palliative care may be required during all of a child’s life or during end of life care and needs to encompass medical, emotional, social and spiritual elements.

Communication

Communication is central to all relationships, particularly when there are difficult decisions to make. Within an organisation a patient advice and liaison service may help support families when they have difficulties in communicating their needs. However, if the situation deteriorates, conflict resolution techniques may be needed and if already embedded with routine paediatric care will help reduce disharmony.[31]

Key points that all services should adhere to are:

- Avoid giving inappropriate expectations.

- Use palliative care teams early, not just for end of life care, but when treatment options are being discussed.

- Recognise that parents will be under severe stress and offer psychosocial support, especially those with children with complex needs or conditions which are life changing or life limiting

- Equally support practitioners by the bedside who may be caught up in the conflict.

- Assign a Lead Clinician role to ensure continuity of information and understanding.

- Develop skills within your service to recognise the development of conflict.

- External expert advice may be helpful, including ethical and legal services and consideration of early involvement of mediation services.

Examples

Enhanced Medical Home Program[32][33]

The introduction of a same day responsive service delivered by a core group of health care professionals who interacted regularly with a wider MDT on behalf of a group of children with medical complexity reduced the unscheduled care needs for ED visits and utilisation of both hospital and PICU beds. The core group identified as the primary care team included nurses and respiratory paediatricians alongside a social worker and dietitian. The wider MDT included organ specialists such as gastroenterologists and neurologists. Sustainability and scalability proved effective in a follow up group.

Buurtzorg model[34]

Predominantly embedded in adult care to provide horizontal integration with patient-centred home care and a focus on small team working to facilitate relationship building, sense of responsibility and ownership of helping improve health outcomes. Responsible individuals are health care providers who also negotiate the social care system for their ‘clients’ to minimise gaps in knowledge and help coordinate their needs.

Care Mapping

Families and children with complex medical problems work with health care professionals to produce a care map which is a visual representation of services and people involved in caring for their child. This has been demonstrated to improve engagement, flatten hierarchy, improve communication and aid understanding of who is involved, focusing on medical, social and mental health needs. An example of this is Boston Children’s Hospital.[35]

There has been an unprecedented increase in emergency department attends in the last 15 years with a 58% increase between 2007 to 2016 and a similar increase predicted by 2030.[36] Year on year the number of children presenting to the emergency department with minor ailments increases by 5%.[37] The majority of the clinical episodes are for minor illness with discharge within four hours for the majority; with < 20% admissions.

Integrated care systems are tasked with reducing unwarranted clinical variation in quality and access to services, with vertical integration between those organisations outside of hospital such as primary care into secondary care. A practical approach is to look at patient flow across a system and produce solutions that engage across places and embed change to resolve the following:

- Increasing demand for primary and secondary care which is unsustainable

- Avoidable access to primary and secondary care

- Uncoordinated care between healthcare settings

- Confused patient (parent/carer) knowledge about when and how to access appropriate services.

A 2010 review from The King’s Fund, entitled “Avoiding hospital admissions: what does the research say?”[38], identified three broad interventions that appear effective at reducing presentations to primary care and emergency admissions: integrating health and social care, integrating primary and secondary care, and patient self-management. There is a core group of minor illness that make up the majority of care episodes, allowing educational packages to be developed that can empower families to self-care and ensure consistent messaging from healthcare professionals when advice is sought. The information can be provided in a digital format or paper with families being equally divided as to what they would prefer.

Examples

Healthier Together Program

A multi-professional and provider group across Hampshire developed a digital web-based resource that was externally facing to provide accessible and consistent information to families, young people and health care professionals with an initial emphasis on the core reasons for a child to present with mild to moderate illness. The aim was to integrate services, empower families to self-care and reduce the unscheduled care attends across the county. Success was demonstrated by a reduction in primary care visits, ED attends and patient/family positive feedback. Adaption and adoption of this resource is currently happening across other systems and a national group has been developed for further iterations such as that within South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw.[39]

Ambulatory Care Experience

Healthcare professionals in Bradford have developed integrated care pathways for acute medical problems in children. These are delivered by paediatric nurses trained in enhanced skills and ensure effective clinical governance, with pathways for each condition. Consultant-led paediatric ward rounds include the children in the hospital at home service, and digital technology is used for review if needed. A reduction in bed days and improved family knowledge about specific medical conditions such as asthma has ensued.[40]

North Staffordshire Hospital@Home services

Developed over a decade ago with the support from primary care, emergency department and paediatrics, a team of twelve trained nursing staff receive referrals for common paediatric conditions from primary care, the regional emergency department and stepping down care from inpatient paediatrics to facilitate home care and early discharge. The successful service has grown, now seeing approximately 450 children a month with excellent feedback.

HandiApp

Staff at Musgrove Park Hospital identified common reasons for attendance at emergency departments and developed an app which provides clear pathways for common paediatric acute illness that has since been promoted by many hospitals and primary care settings to improve health literacy and self-care.

Infants and children who are acutely critically unwell require urgent recognition that their symptoms and signs are potentially life threatening and immediate treatment is required. This means parents and carers having the information to recognise how unwell their child is, knowing something needs to be done, and the health services being available to meet their needs. The health literacy of parents and availability of information for families is crucial in meeting these needs. Primary care staff similarly need to recognise an ill child and have the skills and tools to enable the necessary action. Not all children who present are physically unwell, with mental health problems in children increasing in number and severity.

Early warning and rapid deterioration

For health care providers, a tool that enables rapid communication of the child’s condition and allows assessing deterioration is required across systems. Local use of tools such as paediatric observation priority score (POPS) is an emergency and urgent care checklist which is used in emergency departments and is safe and effective at identifying unwell children, however it is not used by primary care, 111 or 999. A common language is needed and in adults early warning scores have been developed which have ensured care is given earlier with improved outcomes whereas currently in paediatric no similar national paediatric early warning score exists.

The good news is that in England, a national paediatric early warning score (PEWS) group has been convened by NHS England, with support from RCPCH and RCN. The National PEWS Programme Board was originally established in June 2018, with the ambition to develop a consistent approach and common language to promptly recognise and respond to the acutely ill or deteriorating infant, child or young person. In 2020, this programme became part of the NHSE SPOT Programme (System-wide Paediatric Observations Tracking). This programme is looking at how to introduce an adapted PEWS into community settings, including NHS111, ambulance services and primary care. National roll-out is expected throughout 2021.

Paediatric critical care

Critically unwell children may require stabilisation and transfer to another place for definitive treatment or on-going care. This requires transport services for both neonates, children and young people to be embedded in networks to facilitate a system wide approach and has been facilitated by operational delivery networks across regions. With the advent of integrated care systems (ICS) it will be important to understand on what footprint care for acutely unwell children is commissioned, the direction of patient flow and how they fit with existing operational networks. There are a number of practice examples for how high dependency care can be incorporated into the core business of a paediatric critical care (PCC) network within the RCPCH standards for high dependency care.[41]

The current model of care for an acutely unwell child may be through primary care, 111, 999 or walking into an urgent treatment centre or emergency department. Historically 111 have not been staffed by paediatrically trained call handlers with algorithms used not being sensitive or specific enough to enable appropriate care for all – resulting in many being directed to emergency departments unnecessarily. Having paediatric trained staff available would improve recognition of seriously ill children as well as directing others more appropriately. A pilot of this has been underway throughout 2020, with a role description promoted through RCPCH members, and we’d encourage close attention to be paid to the evaluation with a view to national roll out and continuation.

The RCPCH Facing the future- standards for children and young people in emergency care settings identified many gaps in provision which need to be rectified and it is crucial that emergency departments have the staff available to deal with paediatric emergencies.[42]

Short-Stay Paediatric Assessment Units (SSPAUs) are where much of the care for the acutely unwell child now occurs. They are present, with a variety of different naming used, across the UK, usually either co-located with the emergency department or near the paediatric ward. RCPCH have standards for these units, which provide some national service quality indicators.[43] The presence of an SSPAU can result in an overall reduction in the number of inpatient admissions, a higher turnover of patients and reduced length of stay due to earlier discharge when compared with other inpatient environments. Patients may also be referred to community services earlier with well-integrated services. The benefits of the service should extend to improved patient and family experience, however there is currently no national way of measuring the impact of these units in relation to this. This could be measured by providing a platform for children and young people and their families to provide feedback on the service. More broadly, SSPAUs have been shown to be effective in delivering care which has been rated favourably by parents of patients using these services, including a greater level of satisfaction and reports of reduced anxiety.

Patient flow

Patient flow through emergency department and acute assessment units: these areas depend on patients moving through them – and with significant increase in patients attending and not all requiring admission, alternative models have been developed to support children being seen quickly. Primary care staff are often now present in emergency departments, seeing children with minor ailments. This is facilitating early discharge and ensuring families see that prehospital management is possible to support a different approach when their child is next ill. Some EDs are also discharging into hospital at home models where paediatric trained nursing staff will review the child and prevent an admission. An education package is used to promote self-care for the future.

The landscape of urgent and emergency care provision for children has changed significantly in recent years and continues to evolve at pace, albeit with much complexity and variation across the UK. This has been further exacerbated by COVID-19, with 60-80% reductions in ED attends experienced.[44] As a result of this, paediatric staff now looking to work in an integrated way with NHS 111 and primary care to maintain less attends whilst ensuring good clear advice is given to help support management.

Neonatal care

Alongside the patient segments we have just been through, we felt it important to have a separate section on neonatal care to complete our section on taking a whole population approach to care.

The future of neonatal care in the UK needs to involve three key components. Firstly, there should be an application of the known, up to date evidence to optimise the outcome for women during pregnancy, delivery and the wellbeing of their newborn. The National Neonatal Audit Project is a great starting point, as are the various programmes to reduce mother and infant separation. Many units are proud of their performance in these audits, with high percentages for the various domains. However, we don’t at the moment know how many mothers and babies get every health care optimising outcome. While antenatal steroids may be given to 89% of premature deliveries, antenatal magnesium sulphate given to 78% and of those babies being admitted, 92% have temperature of between 36.5 and 37.5 degrees, all sounds like we are doing well. However, it could be that up to 41% (11%+22%+8%) of babies admitted do not get all three interventions and suddenly that is not so shiny. We need to start measuring the entire journey in addition to specific way points.

Parents need to be at the centre of our care. Many units are making great strides in this, but until we are able to offer the single family room experience for the whole neonatal stay, we are just engaged in window dressing. What is needed are much more spacious neonatal units with optimum staffing, which will require investment.

We should be using the cutting edge of technology, rather than struggling with concepts from last century. It is unlikely that on most neonatal units that from one screen you could look at the x-rays, the monitor feed, the ventilator settings, nursing observations and the patient. There is technology now which can extract reflected sound from the vibrations of plants on high speed video, or count the pulse by the colour change seen in skin perfusion. And yet, for most of us working in neonatal care, there is a screen for the monitor, one for the ventilator, another application for the nursing observations. Even if you are lucky enough to have all of those in an electronic patient record, can you get them all on the same screen, with a good enough resolution to read them and see the x-rays at the same time? More often that not, the processor is unable to action the three simultaneous things. We need to find ways to ensure that neonatal units are the prioritised for full integrated systems, which allow remote monitoring, seamless interconnectivity of multiple software packages and computing infrastructure. With the correct connectivity, it may be possible for neonatal consultants to conduct a ward round across several neonatal units, without even leaving their office.

Meanwhile, the low limit of gestation at which resuscitation is being offered is lowering. We are now discussing this at 22 weeks gestation. With development of small equipment, alternative strategies could see us pushing this further down. We are still a long way from artificial placentas and uterine environments for humans, but the foetal lambs in bags full of artificial amniotic fluid are doing surprisingly well.

Overarching service considerations

Throughout this section we have discussed care in hospitals including emergency departments, acute assessment units and paediatric wards, primary care practice, emergency response (111 and 999) and patient homes in the main. Children in respite and hospices should have the same access as those at home if knowledge and care maps are in place. We have a gap in knowledge about how best to provide care in the state care system. There are other places we need to consider to ensure all opportunities are used to improve health outcomes. These include custodial, homeless/refugee, women’s shelters and non-health places such as in schools, nurseries, mother-baby groups, youth centres and religious organisations.

Common barriers to care include poor health literacy and communication issues – with language barrier being one of the greatest obstacles to accessing healthcare resources in emergency departments. Language concordance has been shown to improve care and serves as a window to broader social determinants of health that disproportionately yield worse health outcomes among patients with limited English proficiency.[45]

Care models need to reflect patient flows and may differ based on rurality or urban living but should all be part of a system response. Consistency of any offer needs to occur across a working week to ensure families are aware of what is available and when. Services need to reflect cultural identities and be delivered in a culturally competent way which reduces bias and inequity.

Impact of innovation and technology

The current coronavirus pandemic has ensured rapid deployment for digital technology to deliver virtual consultations. These have the opportunity to reduce unnecessary travel, loss of schooling and supporting families who work. However, any service change needs to be appropriately evaluated to ensure that it is not detrimental to health care outcomes or if there is a disproportionately negative effect on some individuals due to inequalities in access to technology, place of residence and broadband as well as the ability to communicate effectively in this way.

Key components of any paediatric service

We are highlighting the following as key components of any paediatric service, regardless of complexity. We encourage local teams to look at this section for support when implementing any of the suggested services.

We all work in teams, with responsibility for patient care no longer being held by one individual but collectively. This is partly in response to changes in the way paediatricians work with shorter shifts and handovers. Consequently, for any service delivery model to be effective we need to be aware of the importance of how teams form and their effectiveness. When any new team is developed it goes through a number of common stages known as forming, storming, norming and performing – and if the team formed is ‘good’ then there is usually a period of mourning as when you leave as you miss it. What people forget is that when you have new team members you have to make time to integrate or you may not be as effective.

Teams are more than the sum of the individual and are more productive, effective and innovative when they routinely take time out to reflect upon what they want to achieve and how they should do it.

Key elements for effective team working

- Clear, agreed vision and challenging objectives

- Role clarity

- Positivity, optimism, cohesion and compassion

- Effective communication and constructive debate

- Enthusiastic and supportive inter-team working

The risk of not giving time for this is to become a dysfunctional team with

- Inattention to results

- Avoidance of accountability

- Lack of commitment

- Fear of conflict

- Absence of trust

Only by taking the time to identify which, if not all, of the dysfunctional traits are affecting a team’s performance and then taking immediate corrective action to build a more cohesive and accountable team will health outcomes improve. There is evidence form the NHS staff survey that the more functional teams you have in an organisation then the less errors, team stress and injury that occur with improvement in patient outcomes, with a 5% increase in staff working in real teams resulting in a 3.3% drop in mortality.[46]

“Evidence shows that in any team, the mix of professions and practitioners must be able to respond to the needs of the population concerned, while still being small enough to allow members to know each other.” – Prof. Michael West for the King’s Fund.[47]

In the UK we have a diverse society, and this is increasing. In 1991 6% of the population was from a non-white ethnicity and in 2011 it was 15%. The projection by 2030 is that it may well approach 30%. We also have a diverse population in relation to financial situation and level of deprivation. The care we offer needs to embrace these factors and consider who is best placed to offer it.

Equity of care means offering what a family needs, which may not be the same for all, in order to achieve the same outcomes. Interpersonal aspects of care appear to change with patient demographics and hence we may need to tailor consultations dependent upon age, sex and ethnicity.[48] This means we need to have a paediatric workforce that offers diversity in professional background to enhance richness as well as diversity in ethnicity, gender, age and other characteristics.

Delivery of care can be performed by many health care professionals and the roles of paediatricians and doctors have recently been redefined with an emphasis on leadership and co-ordination. There are new professional groups such as advanced clinical practitioner and physician associate that build on the roles of advanced nurse practitioner and specialist nurse, with all contributing to a team approach that relies on skills and competencies being matched to care need.

When you are including new professional groups there a number of themes which need to be considered, focusing on the individual, interpersonal and organizational, as exemplified from qualitative surveys undertaken when incorporating physician associates into the workforce.[49]

There are many definitions of patient centred care but the International Association of Patient Organisations identifies ‘respect for patients needs and preferences’ as central to delivering person centred health.[50] Person centred care is synonymous with a moral imperative to deliver health care that meets the physical, emotional and social needs of an individual, incorporating their values and ensuring through engagement the best possible patient outcomes.

Unconscious bias prevents all from potentially accessing the same services and we need to minimise impact by being aware of human factors such as tiredness that may prevent us from always delivering the care to which we aspire. The six main pillars of medical ethics are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice, dignity and truthfulness. The new General Medical Council guidance on decision making and consent[51] has a clear focus on truthfulness, which means ensuring that what we offer is not only done so with good conscious but with the knowledge that it will have a positive effect for that specific patient – and if we do not know this to be the case, we have an open conversation regarding it.

Consent is given during a discussion about management options and having the patient and family voice is of paramount importance to ensure we improve health for that child. Patient centred care is acknowledging that the family is the child’s main source of strength and support and the perspectives offered by the child and family are central to delivering high quality decision making. The child’s voice must also be heard as we know that even primary school children fail to engage with treatment options due to concerns over being different and potentially excluded for social encounters.

Children, young people and family engagement within services is vital to be able to understand what matters to them, to collate and unpack experiences as service users, as well as creating space to think collaboratively through participation or co-design approaches to develop services and identify solutions.

The NHS Constitution (2013)[52] is clear that patients and the public have the right to be involved in the planning of healthcare services commissioned by NHS bodies, and the development and consideration of proposals for changes affecting the operation of those services, with “service users coming together to shape services with staff”. This is legislated through section 242(1B)[53] of the National Health Service Act 2006 as amended by the Local Government & Public Involvement in Health Act 2007. There are further examples of legislative drivers for engagement in the RCPCH Engagement Legislation briefing (2017)[54]

RCPCH keeps children and young people at the centre by having a rights based approach[55] where we take seriously our role in supporting children and young people’s dignity, participation, development, non-discrimination and best interests within engagement in health and paediatric service design, their right to interdependence and indivisibility and our role in being transparent and accountable across their engagement. The foundation is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which helps countries, organisations and individuals know what needs to happen to give all children and young people the best start possible. The articles help children and young people be safe from harm, have chances to learn and develop, become an individual and get the support needed to thrive.[56]

Defining the approach

Engagement refers to the process of participation and involvement, where children and young people are given the chance to be educated about their rights and opportunities to engage, collaborate with others to share their views, become engaged in shaping policy, practice and identifying / leading solutions and create change through their voices, wishes and needs and those of other children and young people. Strategic voice relates to children and young people’s involvement in informing and influencing our work.[57]

Children and young people for RCPCH’s engagement activity is defined as infants, children, young people, young adults up to their 25th birthday and their advocates (parents, carers, families, friends, healthcare professionals, support workers – plus others) with the primary focus being supporting and encouraging the voice and views of children and young people. It’s important that each setting thinks about their definition of engagement, about whether the definition needs to be adapted and to consider the variety of models or approaches to be used for different groups (e.g. infants, children, young people, parents, extended families) and subgroups (e.g. LGBT, young carers). This will ensure the engagement meets both the needs of the group and the service, whilst retaining a rights-based approach.[58]

We advocate a mixed methods approach to engagement and co-design from micro-volunteering in clinic chats[59] children and young people can share their experiences to help inform policy or processes, in one off taster sessions or in regular projects that meet weekly or monthly. Every voice and every view counts, whether it has been shared through art based activities, using communication aids for those who are nonverbal, through online responses to text consultations or in face to face conversations and workshops.

In developed child and family engagement approaches, it is important to consider equality, diversity and inclusion within planning, to be able to engage and involve children and young people from a range of difference experiences, ages, backgrounds, locations and specialist experiences. We have our own diversity definition that we use when planning a project, so that we can make sure we have a range of diverse voices actively involved.

Diversity for RCPCH &Us work includes working with three different groups:

- Universal: involving children and young people through open access sessions where health experience is not a pre-requisite for involvement e.g. schools, youth groups, outreach. Locations/settings are chosen to represent different ethnicities, socio-economic backgrounds and ages

- Targeted: children and young people with a shared experience e.g. Young carers, special school, children in care

- Specialist: children and young people with a specific healthcare experience accessed through a health setting / health-based condition forum e.g. clinic chat in a respiratory clinic, sickle cell forum[60]

Operationalising the approach

We bring together all three groups through all stages of the engagement programme (educate, collaborate, engage and change) so that they are able to learn from each other, meeting new friends and networks, as well as preventing group think or bias from one particular set of experiences. It is as important to hear the expectations of those who have not yet used a paediatric service as it is to hear from those who have a lifetime of experiences to share.

When we move to operationalize an engagement activity, we consider the following when planning to ensure that our work is inclusive and accessible:

- Communication needs/preferences e.g. interpreter, large font handouts, easy read/Widgit

- Accessibility needs e.g. note taker needed, 1:1 needed, ramp required

- Contact management e.g. for children/young people in care or adopted, there may be occasions when they can’t mix with siblings or family members

- Health needs e.g. personal care worker, low energy activities, must be dial in as immuno-suppressed (e.g. CF)

- Developmentally appropriate e.g. age, cognitive, sensitive topics

- Wider inequalities e.g. financial (always provide paper/pens/pre-paid travel), food insecurity (always provide food/drink)

- Identity based awareness e.g. LGBTQIA+/BAME/Disabilities/Faith & Beliefs

RCPCH has a suite of support for services looking to embark on child and family engagement for the first time, or for those who are developing their engagement offer, with 60+ resources coproduced with children and young people from RCPCH &Us at www.rcpch.ac.uk/and_us

A key component of any paediatric team needs to be assessing outcomes, with a focus on how you will define your team effectiveness for children, how you assess it with key indicators, and data collection requirements with inclusion of patient feedback. These are known as patient related outcome measures and patient related experience measures (PROMS and PREMS). It is also important to understand your own team climate. As a service becomes developed at a system level, spanning boundaries with integrated care it may well be made up of multiple teams, some of which will be within an organisation and others of which will have members from different organisations.

However, no matter what the make-up, the attention must remain on outcomes with a focus on five domains[61]

- Management of the ‘condition’ and improved health outcomes

- Patient safety

- Activity and patient flow

- Patient and parent/carer experience

- Staff experience

More information about QI activity is available from RCPCH QI Central[62] and the Health Foundation.[63]

References

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019) https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/

Rigby E, Hagell A, Marion D. Getting health services right for 16-25 year olds. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2021 ; 106 (1) : 9-13

Royal College of Physicians Toolkit 13 acute care for adolescents and young people. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/acute-care-toolkit-13-acute-care-adolescents-and-young-adults

Care Quality Commission (2020) Out of sight- who cares ? A review of restraint, seclusion and segregation for autistic people, and people with a learning disability and/or mental health condition. Care Quality Commission. https://cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20201218_rssreview_report.pdf

Klaber RE, Blair M, Lemer C, Watson M. Whole population integrated child health: moving beyond pathways. Arch Dis Child. 2017 Jan;102(1):5-7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310485. Epub 2016 May 23. PMID: 27217582.

RCPCH (2020) Paediatrician of the future: delivering really good training. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/rcpch-paediatrician-of-the-future-delivering-really-good-training.pdf

House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee. First 1000 days of life. Thirteenth report of session 2017-19 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmhealth/1496/1496.pdf

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019) https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/

Children and young people’s health outcomes forum: report of the public health and prevention sub-group https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216854/CYP-Public-Health.pdf

NHS Healthy Child Programme. http://www.healthychildprogramme.com/

Surrey Heartlands. Women and children’s care https://www.surreyheartlands.uk/our-priorities/clinical-priorities/women-and-childrens-care/

Healthier Together https://what0-18.nhs.uk/

Reach out and read https://reachoutandreadtexas.org/

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Prevention and management of dental caries in children dental clinical guidance. https://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SDCEP-Prevention-and-Management-of-Dental-Caries-in-Children-2nd-Edition.pdf

Male A, Farr W and Reddy V. Should clinical services for children with possible ADHD, autism or related conditions be delivered in an integrated neurodevelopmental pathway. Integrated Healthcare Journal. 2020

Seward RJ, Bayliss DM and Ohan JL. The Childrens Social Vulnerability Questionnaire (CSVQ) : Validation, relationship with psychosocial functioning, and age related differences. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2018 ; 18 : 179-188.

Jacob G, Heuvel M, Jama N et al. Adverse childhood experiences : Basics for the paediatrician. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2019 : 30-37

Watson P. How to screen for ACE’s in an efficient, sensitive and effective manner. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2019 : 37-38.

RCPCH. Why children die (2014). https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2017-06/Why%20children%20die%20-%20Death%20in%20infants%2C%20children%20and%20young%20people%20in%20the%20UK%20-%20Part%20A%202014-05.pdf

RCPCH. SMOMED-CT. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/snomed-ct-how-guide-clinicians

Wolfe et al. Child health systems in the United Kingdom (England). The Journal of Pediatrics. Volume 177 Supplement, 2016.

Beat Asthma website – https://www.beatasthma.co.uk/

Newham JJ, Forman J, Heys M et al. Children and Young Peoples Health Partnership (CYPHP) Evelina London model of care: protocol for an opportunistic cluster randomised controlled (cRCT) to assess child health outcomes, healthcare quality and health service use. BMJ Open. 2019;

The CoLAB. Why the need? https://www.colabpartnership.org.uk/pages/7-why-the-need

Tamara D, Simon MD, Lawrence Cawthorn M et al. Paediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm: A New Method to Stratify Children by Medical Complexity. Paediatrics. 2014; 133 (6): e1647-e1654.

Adams S, Cohen E, Mahant S et al. Exploring the usefullness of comprehensive care plans for children with medical complexity (CMC): a qualitative study. Biomed Central Paediatrics. 2013 ; 13: 10-21.

Donnelly ES, Shaw E, Timoney P et al. Parents Assessment of an Advanced-Practice Nure and Care Coordination Program for children With Medical Complexity. Journal of Paediatric Health Care. 2020; July/August: 325-331

RCPCH Facing the Future Standards for Children with Ongoing Health Needs (2018). https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-04/facing_the_future_standards_for_children_with_ongoing_health_needs_2018-03.pdf

Together for short lives – website https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/

NICE Quality Standard QS160. End of life care for infants, children and young people. (12 September 2017)

Linney M, Hain Rd, Wilkinson D et al. Achieving consensus advice for paediatricians and other health professionals: on prevention, recognition and management of conflict in paediatric practice. Archives Disease Child Health. 2019; 104 (5): 413- 416.

Mosquera RA, Elenir BC, Samuels CL et al. Effect of an enhanced Medical Home on Serious Illness and Cost of Care Among High-Risk Children with Chronic Illness. A Randomised Clinical Trial. Journal of American Medical association. 2014; 312 (24): 2640-2648.

Avritscher EBC, Mosequera RA, Tyson JE et al. Post-Trial Sustainability and Scalability of the Benefits of a Medical Home for High-Risk Children with Medical Complexity. Journal of Paediatrics. 2019; 206: 232-9.

The Buurtzorg Model. https://www.buurtzorg.com/about-us/buurtzorgmodel/

Boston Childrens Hospital, https://www.childrenshospital.org/integrated-care-program/care-mapping

RCPCH (2018). Child Health in 2030. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/child_health_in_2030_in_england_-report_2018-10.pdf

NHS Digital, Hospital Episode Statistics for England. Hospital Accident and Emergency Activity. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-accident–emergency-activity

The King’s Fund. Avoiding hospital admissions. (2010) https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Avoiding-Hospital-Admissions-Sarah-Purdy-December2010.pdf

Healthier Together website https://what0-18.nhs.uk/

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS. The ACE service https://www.bradfordhospitals.nhs.uk/the-ace-service/

RCPCH 2014. High dependency care for children: time to move on. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-07/high_dependency_care_for_children_-_time_to_move_on.pdf

RCPCH Facing the Future: standards for emergency care. 2018 https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-06/FTFEC%20Digital%20updated%20final.pdf

RCPCH Standards for short stay paediatric assessment units. March 2017. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/SSPAU_College_Standards_21.03.2017_final.pdf

Isba R, Edge R, Jenner R, et al. Where have all the children gone? Decreases in paediatric emergency department attendances at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 Archives of Disease in Childhood 2020;105:704.

Molina RL & Kasper J. The power of language-concordant care: a call to action for medical schools. BMC Medical Education. 2019; 19 (1): 378.

Lyubovnikova J, West MA, Dawson JF & Carter MR. 24-Karat or fool’s gold? Consequences of real team and co-acting group membership in healthcare organisations. European Journal of Organisational Psychology. 2015; 24 (6): 929-950.

The Kings Fund. How to build effective teams in general practice. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/effective-teams-general-practice

Croker JE, Swancutt DR, Roberts MJ, et al. Factors affecting patients’ trust and confidence in GPs: evidence from the English national GP patient survey. BMJ Open 2013;3: e002762. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2013-002762

Sam Roberts, A ‘What can you do then?’ Integrating new roles into healthcare teams: Regional experience with physician associates. Future Healthcare Journal 2019 6 (1) 61

Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011 Oct;23(5):510-5. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr024. Epub 2011 May 16. PMID: 21586433.

GMC (2020). Decision making and consent. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/updated-decision-making-and-consent-guidance_pdf-84160128.pdf

NHS Constitution. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-constitution-for-england

National Health Service Act 2006. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/41/contents

RCPCH &Us Engagement Legislation. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/And_Us_-_Legislation_briefing.pdf

UNICEF. Becoming a UNICEF child friendly city or community https://www.unicef.org.uk/child-friendly-cities/child-rights-based-approach/

RCPCH. Rights matter: what the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child means to us. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/rights-matter-what-un-convention-rights-child-means-us

Sparrow, E & Linney, M (2020) ‘RCPCH & Us: Improving healthcare through engagement’ in Brady, L-M. (eds.), Embedding Young People’s Participation in Health Services: New Approaches. 1st ed., Bristol University Press.

RCPCH. How to write a children and young people’s engagement plan – RCPCH &Us https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/how-write-children-young-peoples-engagement-plan-rcpch-us

RCPCH &Us Recipes for engagement – recipe 16. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/recipes_for_engagement_2018.pdf

Sparrow, E & Linney, M (2020) ‘RCPCH & Us: Improving healthcare through engagement’ in Brady, L-M. (eds.), Embedding Young People’s Participation in Health Services: New Approaches. 1st ed., Bristol University Press.

RCPCH 2016. Service Level Quality Improvement Measures for Acute General Paediatric Services (SLQMAPS). https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/SLQMAPS_Main_Report_v1.0_0.pdf

RCPCH QI Central website https://qicentral.rcpch.ac.uk/

The Health Foundation Q community. https://www.health.org.uk/what-we-do/supporting-health-care-improvement/partnerships-to-support-quality-improvement/the-q-community